New financial-tech services let employees withdraw a portion of the money they earn, as they earn it.

It was a find—a better apartment, with a lower rent. Amber Thompson jumped on it and gave her landlord 30 days' notice.

Shortly before the 28-year-old Gonzales, La., hospital recruiter was scheduled to move, she found out that her landlord required 60 days' notice. She would have to pay an extra month of rent for her old place on the same day she’d be paying the first month’s rent on her new place, on top of her other bills. Her paycheck wouldn’t arrive in time to cover it all.

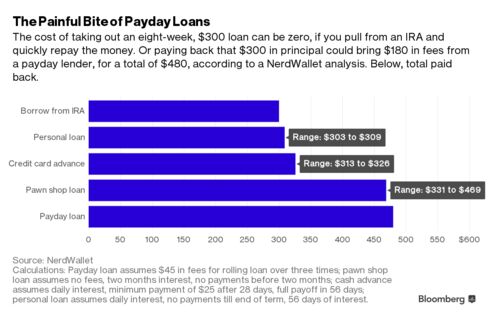

Cash crunches such as Thompson's lead many people to pile up credit-card debt, bounce checks, or turn to payday lenders, which charge high interest rates and fees for making loans against your paycheck. The result can be additional fees for late payments and overdrafts in a financial spiral.

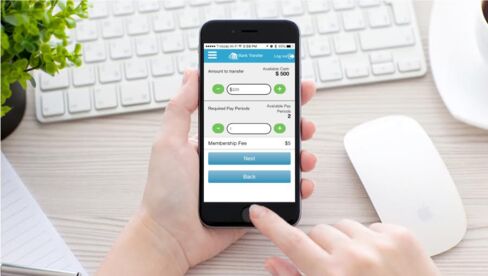

Thompson had a further option. Her employer, Baton Rouge General Medical Center, had signed on with a service called PayActiv that lets employees withdraw a portion of the money they earn, as they earn it, without waiting for a paycheck. The transaction fee is $5. Thompson, one of 400 or so employees who enrolled to use the service, walked to the PayActiv ATM in her building and took out $400.

PayActiv just won a Best of Show award at FinovateSpring 2016 for its use of technology to ease the "cash flow struggles of working families." (A picture of its app appears below.) It is one of a raft of young financial technology companies with such names as FlexWage, Activehours, Clearbanc, and Even that were launched to fill a financial gap.1 Weekly and biweekly paychecks don't fit the way many people work any more. In a sign of the times, ride services such as Lyft and Uber have rolled out Instant Pay and Express Pay services for their drivers

“So many of our financial services today are based on a stability of lifestyle and income that very few people have now,” said Ryan Falvey, who oversees the Financial Solutions Lab at the Center for Financial Services Innovation. The Lab supports companies working on creative services that help Americans improve their finances.

“Everyone has this mindset that waiting to get paid is somehow good," said PayActiv's chief executive officer, Safwan Shah. "Is waiting to get paid something that can create forced savings, or does it cause problems for low-income people? We’ve done studies to prove that what we are doing is actually helping people save more.”

That doesn't mean having constant access to your earnings is risk-free. Activehours, which lets consumers choose what to pay for transactions through what it calls "tips," helps employees with budgeting, said Ram Palaniappan, CEO. “If you need to spend, you check if there are earnings in the app, and if there aren’t, you need to work more before you spend,” he said. “It’s very much like business, trying to make revenue meet expenses.”

Moreover, the percentage of earnings that employees can take, and how often they can take it, may be limited by employers. For now, Baton Rouge General caps withdrawals at 50 percent of wages earned and a maximum of $500. An employee can’t take out another loan until the first one is repaid out of his or her paycheck.

Other companies may set the limit at 75 percent to 80 percent of earnings and limit the service's use to once per pay cycle, said FlexWage CEO Frank Dombroski. He founded the company after six years at JPMorgan, where he managed the firm's commercial payments solutions business.

The pitch to employers is less financial stress on employees and improved productivity. The service is often positioned as a financial wellness benefit that can increase retention. PayActiv's Shah said being able to tap earnings this way can lead to better financial behavior. He compared it to grazing on food, rather than bingeing.

“Access to money in small dollar amounts when it’s needed has far more value than waiting to be paid and, in the interim, getting into a debt trap, à la payday lending,” he said.

It’s too early to measure the results, though some companies offer positive anecdotal evidence.

At Baton Route General, Chief Financial Officer Kendall Johnson was leery of PayActiv. “We were very concerned that this would become another form of a recurring loan,” he said. So far, though, employees are using it when they have cash flow problems and need such things as car repair, he said, not turning to it every month. He's seen a decrease in the number of employees using check-cashing sites and payday lenders, which call Baton Route General to verify employment.

Michael Fox, chief executive officer of Goodwill of Silicon Valley, says PayActiv's service has been “fairly successful” in a pilot program with about 300 employees. When Fox was in southeast Asia getting a global MBA, he saw how small financial mishaps could create disasters. “Something happens in a family where they need $200 to $300 now, and it starts this whole domino effect, and can even lead to unemployment,” he said.

A few years ago, Fox saw one employee go from owing about $500 to a payday lender to owing several thousand dollars within a few months, he said. Goodwill gave the employee a loan so he could pay off the high-interest loan.

These early-stage companies need to scale up while keeping the cost of acquiring customers low, and they are likely to face increased regulatory scrutiny as the sector grows. Shah said PayActiv has had over a dozen meetings in the past two years with 25 to 30 people associated with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's Project Catalyst "in the spirit of keeping them updated." Project Catalyst's "mission is to encourage consumer-friendly innovation in markets for consumer financial products and services," according to the CFPB website.

Dombroski said FlexWage has been working with Project Catalyst on a study to quantify the impact of financial stress. The CFPB said in an e-mail that it "meets regularly with a range of industry and advocacy stakeholders" but generally doesn't "comment on or discuss specific products."

"I don't think the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has put a broad eye on these companies yet because the numbers aren't there yet," said Sam Maule, digital practice lead for NTT Data Consulting. "The onus is on these companies to educate the regulators."

It also falls to them to educate customers about how the product is meant to be used, said Cherian Abraham, a payment expert at credit-tracking company Experian. "It's harder for companies like these because their customers have been called unprofitable by the traditional financial institutions," Abraham said. "So they have a tougher job."