How cooking is changing medicine.

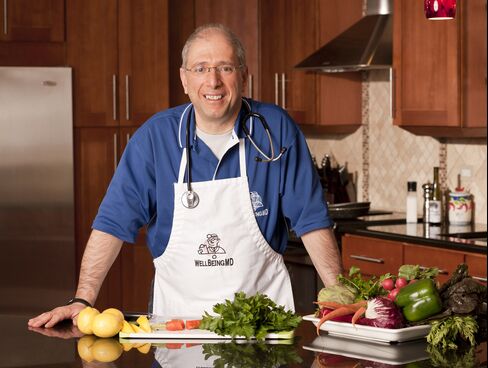

Dr. John Principe in his medical practice's teaching kitchen in Palos Heights, Illinois.

After more than 20 years in practice, Dr. John Principe was ready to quit.

“I was just tired of doling out pills and having people die of the same disease I was quote-unquote treating,” says the 58-year-old internist. While he was helping his patients manage their illnesses, he says, he wasn't changing their lives.

Before walking out the door in 2008, he attended the Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives conference in California's Napa Valley, a collaboration between the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Culinary Institute of America. The conference teaches health professionals about the basics of nutrition and exercise, focusing not only on what to eat but also on how to cook it, topics most medical curricula never touch.

For Principe, it was a game changer. In 2009, he founded a new practice, WellBeingMD, bringing in homemade food and sharing his recipes with patients. He taught cooking classes at a local community center. In 2010, he built a teaching kitchen in his office in Palos Heights, Ill.

“I mortgaged my house to do it,” he says, “but it’s something I believe in.”

Americans are growing increasingly conscious of their health, as diet-related conditions such as diabetes and heart disease remain stubbornly among the top causes of death in the U.S., but many people don’t know what healthy food looks like. Many doctors don’t know, either. More and more, though, are interested in learning how to give practical eating advice, based on the kind of peer-reviewed science they’ve always relied on. Those skills are even making their way into medical school.

Besides keeping the traditional appointments, Principe now leads cooking classes on such topics as digestive health and blood sugar control. Patients prepare their own healthy dishes, like nut milk for those who can't have dairy, or sauerkraut and other fermented foods for gastrointestinal health. One patient in a 2015 YouTube video about his practice says she was sick all the time and didn't know if she would live to see her kids graduate from high school, then recovered her health and lost almost 30 pounds. Another says he no longer needs his statins or his asthma medication. Principe cites a waiting list of more than 500 patients and says he’d love to bring them in but first needs to find a “likeminded” doctor.

He might not have to look far. In the past decade, the Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives conference has been offered 12 times, always meeting its 400-person maximum. It has a waiting list, too.

“They are tutored by world-class chef-educators and shown they can do it,” says Dr. David Eisenberg, who heads up culinary nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan and is co-director of the conference with Greg Drescher, who leads strategic initiatives at the Culinary Institute. “In that experiential moment, I think many doctors are transformed.”

Their own diets, at least, are transforming. In 2013, Eisenberg published a study that tracked the impact on the participating health professionals themselves. Of the attendees that responded to his survey, 58 percent had cooked their own meals five or more times a week before the conference. Afterward, 74 percent did. They ate more vegetables, nuts, and whole grains. Before the conference, only 40 percent had rated themselves as “good or excellent” at helping overweight or obese patients improve their nutritional and lifestyle habits. Three months after the conference, it was 81 percent.

Since 2012, the Tulane University School of Medicine has been teaching medical students, as well as licensed practitioners, how to cook in its own teaching kitchen, at the Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine, led by Timothy Harlan, a trained chef and doctor. The program has been licensed to more than 10 percent of the country’s medical schools. A proponent of the much-studied Mediterranean diet, Harlan wants his students to be able to advise their future patients in concrete terms, even in a short office visit.

“We’re working to create two-minute interventions,” Harlan says, to get a salt snacker to switch from Cheetos to nuts, or an Egg McMuffin lover to try the equally convenient bowl of cereal with yogurt.

Watermelon Aqua Fresca at Principe's practice in Palos Heights, Ill.

As with the Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives participants, a study found that the Tulane med school students participating in the program saw their own diets improve as a result. The same turned out to be true of diabetic community members who had taken the Tulane courses.

Some have made do with a lot less. After a successful pilot program the year before, in 2013, Stanford University School of Medicine’s Maya Adam launched a free online course, through Coursera, of 47 videos on childhood nutrition and cooking. The four- to six-minute videos show Adam cooking in her own home kitchen, explaining what she’s doing, sometimes while carrying a child. More than 250,000 people from all over the world have watched. A study that included 7,422 of them found that participants cooked more often, their meals were healthier, and they enjoyed them more. The school has since turned an existing kitchen into a teaching kitchen, with Adam instructing its first course, and launched a second series, featuring Michael Pollan, with a couple of cameos from Eisenberg.

Nutrition can be taught without a stovetop. At Georgetown University Medical Center, Thomas Sherman, a molecular neuroendocrinologist, has fought to get the subject on the curriculum, finding a place for it in a new, integrative course on metabolism, nutrition, and endocrinology. Now the university is building a teaching kitchen into one of its dorms. It will be "nothing like Tulane’s, but a place where we hope, starting next year, we’ll have demonstrations,” Sherman says, adding, of Tulane's Harlan, “I am just so jealous of everything he is doing down there.”

Each teaching kitchen, and each approach to culinary medicine, is different, depending on resources, patients, time, and the practitioner’s professional and personal background. “If you’ve seen one approach to culinary medicine by one doctor, you’ve seen one approach to culinary medicine by one doctor,” Eisenberg says.

There seem to be just as many ways to get insurance to cover it,1 so doctors are getting creative. Instead of doing individual follow-up visits, Helen Delichatsios, an internist at Massachusetts General Hospital, often sees eight to 10 patients with similar concerns in one 90-minute appointment, addressing at least one of each person’s medical issues and including a 20-minute food demo at the end. She bills each patient to the insurance company as she would for a standard medical follow-up but gets an hour and a half with all of them instead of the 15 minutes she would typically get with each.

Keri Connell, health educator and nutritionist, runs the Ross kitchen

In his practice’s teaching kitchen in Ellicot City, Md., Warren Ross teaches eight to 10 patients at a time about purchasing, preparing, and portioning food as part of an integrative-medicine practice. Patients learn how to pace themselves while eating, too. “We do tasting portions, not full portions, but everyone walks away full,” he says.

John La Puma went farther than Principe, actually leaving medicine to go to the Cooking and Hospitality Institute of Chicago, now Le Cordon Bleu- Chicago. He has a big audience through his website, YouTube videos, seven books, consulting company, and lectures, which he gives to as many as 1,500 people at a time, including clinicians, members of the general public, and the food industry. These talks usually include concrete advice—eat flax seed to lower your cholesterol—and cooking demonstrations.

“Doctors want to know the really tactile things,” says La Puma, who is based in Santa Barbara, Calif. “How do you hold a knife? How do you slice a mushroom without cutting a finger off?”

One doctor-chef has led group demos in conference rooms with little more than what she could carry: knives, a cutting board, and sometimes a portable skillet. Michelle Hauser is a primary-care provider for a low-income community at Fair Oaks Health Center in Redwood City, Calif., a postdoctoral research fellow at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, a graduate of Le Cordon Bleu in Minneapolis, and one of Eisenberg’s early collaborators. She finds that those few tools are enough to show her patients how to cook a whole grain and mix it with chopped fresh vegetables and a homemade vinaigrette, a recipe with endless variations.

These doctors haven’t stopped writing prescriptions, though some say they write fewer than they used to. Principe says he writes so few that pharmaceutical reps don’t even visit him anymore. La Puma likes to use his prescription pad for recipes, but says he usually starts with food as a supplement to medication. Harlan emphasizes the evidence basis in peer-reviewed literature for the culinary counsel he provides, but doesn’t hesitate to give patients the pills they need.

“I am an allopathic physician,” he says. “I will write a prescription for a statin.”

No comments:

Post a Comment