Despite debt, stagnant wages, and sluggish economic growth, young people may yet find a path to prosperity.

Young Americans’ incomes are depressed, their retirement nest eggs are microscopic, and their rate of employment is weak. The trend lines aren’t promising, either, which likely explains why there’s no shortage of pessimism out there. In a Bloomberg poll of Americans age 18 to 35—the millennial generation—47 percent said they do not expect their cohort to live better than their parents. For one thing, it’s hard to imagine outdoing your parents if you’re still sleeping under their roof. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, 15 percent of people age 25 to 34 were living with their parents last year, up from 10 percent 30 years earlier. High home prices and strict mortgage lending standards are prime reasons for many millennials’ failure to launch. “They are priced out of the kind of housing that they grew up in,” says Richard Portes, an economist at London Business School.

Living at home, or living away from home but depending on help from Mom and Dad, keeps many young people from learning how to manage their finances, says Vicki Bogan, an associate professor at Cornell University’s Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management. “You don’t have any ownership, any force to push you to become financially literate,” she says.

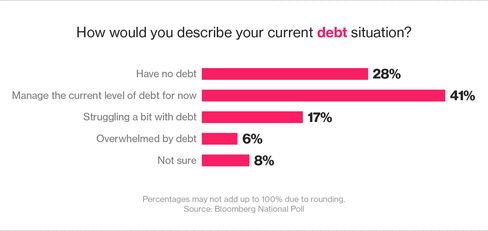

Not all young people have student debt, but for those who do, it can be paralyzing. Jessica Xydias, 25, says she didn’t take out a lot of student loans, “but my husband did. I look at our accounts all the time. It feels crushing and insurmountable.” And the debt crimps their ability to save. While paying off loans, she says, “it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to put money into your Roth account.”

One thing millennials do have in their favor, of course, is time. Modest economic expansion that exceeds population growth “is more than enough to support a higher standard of living for our children over time,” says Gus Faucher, senior macroeconomist at PNC Financial Services. Whether young people dig out from their deficit and end up surpassing their parents’ generation depends on some unknowable things. Will globalization and automation kill or create jobs? Will humankind be saved by nuclear fusion and a cure for Alzheimer’s, or be doomed by climate change, wars over resources, and the crippling cost of elder care?

One way to look ahead—and restore some optimism—is to look back to millennial parents’ salad days. Median wages and assets were higher, adjusted for inflation. But would you trade that life for the one you have? Would you give up your smartphone, your GPS, Google, Amazon.com, fresh peas in winter, and Ford F-150s with aluminum bodies that won’t rust?

It’s just as likely to envision a similar set of innovations 30 years from now that people can’t imagine living without. If so, then no matter what the official statistics say, the best years just might lie ahead.

No comments:

Post a Comment